SEMA News—December 2011

Just Hit Print

Rapid 3-D Manufacturing Comes of Age

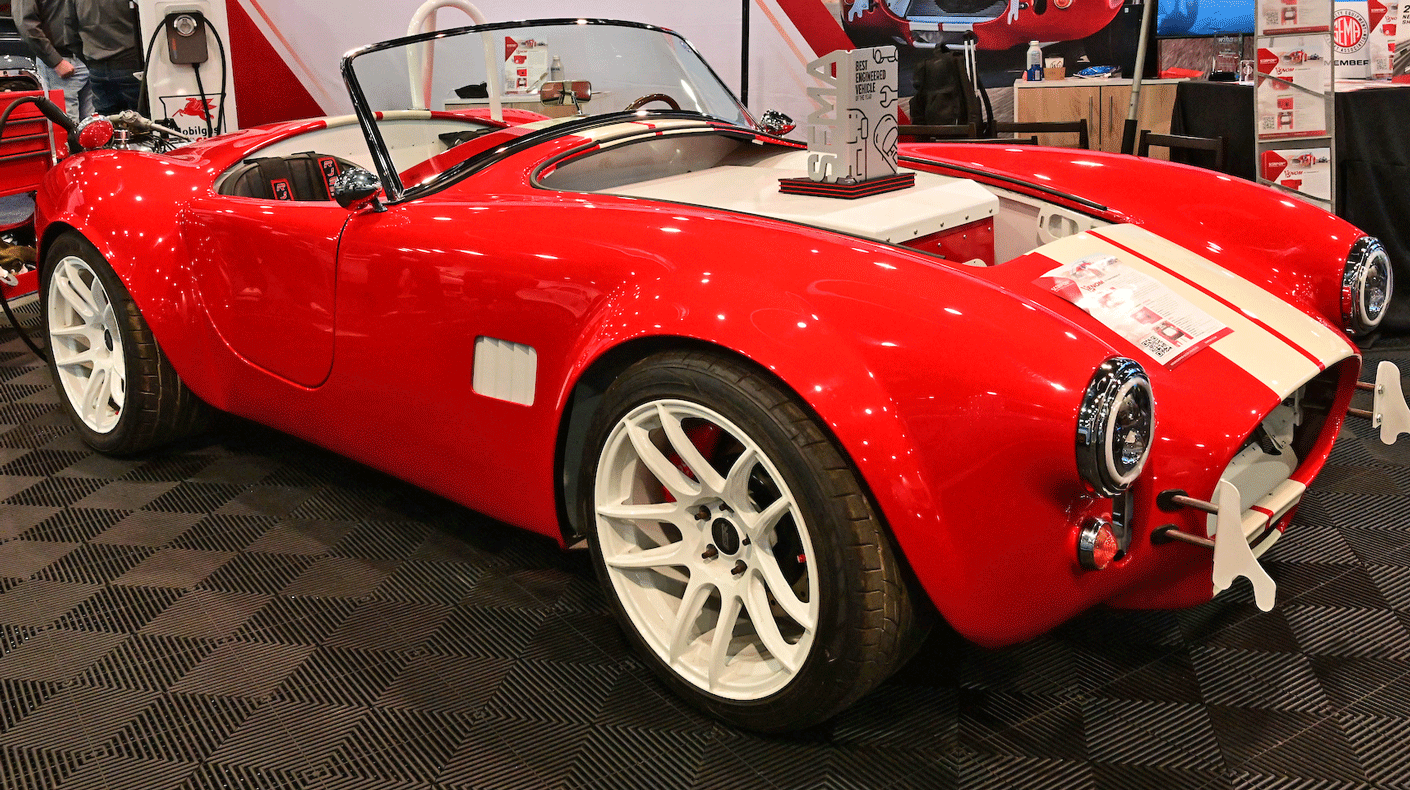

Kor Ecologic founder Jim Kor (background, far left) and his design team gather around their “3-D print” car, first presented to the industry at the 2010 SEMA Show. The vehicle was a hit, especially with fabricators and customizers, who instantly recognized the implications of its novel manufacturing process.

|

|

Technically known as rapid prototyping or additive fabrication, high-end medical, aerospace and automotive designers have used the process for nearly two decades to develop small thermoplastic prototypes and models for research and development purposes. Thanks to recent advances, however, the process is now both refined and cost-effective enough to create finished goods, including manufacturing tools, jigs and fixtures—not to mention end-use parts.

“Any technology takes a while to catch on,” said Joe Hiemenz, spokesman for Stratasys Inc., a Minnesota-based maker of the machines. “I think maybe part of the reason this is taking off now is because the term ‘3-D printing’ has taken hold. That’s an easier term to remember or relate to than rapid prototyping, rapid fabrication, additive manufacturing or any of these other terms that have been used. Lay people seem to get that, although you’re not printing on paper, you’re pulling out a plastic part that’s been ‘printed’ layer by layer.”

Changing Virtually Everything

The reduced cost and varied sizes of 3-D printers are rapidly placing them in the hands of businesses at every level. Pictured are Stratasys’ FDM 900mc (left) and Fortus 360mc units. Some companies also make “desktop” versions for artisans and hobbyists. |

|

|

|

“The thermoplastic is melted and extruded in fine layers—as fine as five thousandths of an inch thick,” explained Hiemenz, noting that such accuracy has now made 3-D printing competitive with injection molding. The liquid plastic continues to be applied layer by layer until there’s a finished part. Overhangs and protrusions are handled by building breakaway or dissolving support structures into the design, which are then easily removed during finishing.

Depending on a product’s size, the entire process can take a few hours or a few days from beginning to end. Plus, as with CNC technology, experts say that 3-D printing is poised to revolutionize manufacturing, placing some level of additive fabrication within the reach of even the smallest of aftermarket businesses or shops.

“Back when prototyping was totally new, it was pretty limited to some high-end applications,” Hiemenz said, “but it quickly spread to the point where you’d be hard pressed to find any manufacturer designing a physical product that doesn’t use some form of rapid prototyping or additive manufacturing, as it’s being called now. Cost is getting down to the point where even consumers are going after these machines. If you are any kind of custom manufacturer—and especially if you’d like your finished part to be thermoplastic—it’s definitely a technology you should look at.”

Indeed, 3-D printers come in a variety of sizes, from desktop units to large machines that are approximately 6x8x4 ft. in dimension. Stratasys units range in price from roughly $15,000–$450,000, and Hiemenz observes that a growing number of manufacturers are designing non-professional units for artisans and hobbyists to use in their studios or garages.

Increasingly, mainstream business media is touting the technology’s potential to forever change the manufacturing world as we know it. As The Economist magazine recently observed: “Three-dimensional printing makes it as cheap to create single items as it is to produce thousands and, thus, undermines economies of scale. It may have as profound an impact on the world as the coming of the factory did.”

This, explained the magazine, is because the additive approach “cuts costs by getting rid of production lines. It reduces waste enormously [and] allows the creation of parts in shapes that conventional techniques cannot achieve, resulting in new, much more efficient designs in aircraft wings or heat exchangers, for example.”

Printing Almost Anything

If all this sounds like hyperbole, consider the Urbee, “the world’s first printed car,” displayed in rudimentary form at the 2010 SEMA Show.

“We were a bit apprehensive because we only had a few body panels,” said Jim Kor, president and senior designer of Kor Ecologic, a company he founded 15 years ago to completely rethink sustainable automotive engineering. “Really, just a stainless-steel frame and two body panels was all we showed.”

The Urbee (an acronym for urban electric with ethanol as backup) was designed from the ground up as a “practical, roadworthy car that runs solely on renewable energy, is environmentally responsible and has universal appeal.”

Initially Kor’s design team opted for 3-D printing to build their 1/6-scale vehicle prototype. Before long, they realized that they could just as easily print fullsize parts for the vehicle at a fraction of the cost. Moreover, the technique also provided timely, high-tech solutions to engineering dilemmas that would have been difficult to overcome with traditional manufacturing. Fiberglass panels alone would have taken months of expensive labor to mold and produce. Additive fabrication created them at a much lower cost in a few short weeks.

The concept definitely wowed the 2010 SEMA Show crowd.

Touted as the “world’s first printed car,” Kor Ecologic’s Urbee vehicle has captured the imagination of the media and industrial trend-spotters alike. The entire car exterior was constructed by “additive manufacturing”—a process recently dubbed 3-D printing. |

|

To Kor, whose resume is also heavy on tractor and commercial vehicle design, 3-D printing is especially apropos for the Urbee since the entire point of the project is to reinvent the automobile based on its purpose today. He said that other ecological vehicle designs are mere attempts to adapt new technologies to a traditional platform. Instead, Team Kor has set out to re-imagine everything as a clean sheet, from the ground up.

As Kor sees it, “Companies are into cars the way they’ve been making cars, and they are huge, huge corporations, so they are slowly refining their offerings.” He goes on to explain that the Urbee design goal was an alternate means to run short, daily errands using the least energy possible. Like engineering a glider, Kor’s group lets physics dictate how the form of the car would follow function. This led to the application of vastly different materials and mechanics to the problem. The vehicle’s market appeal was of negligible importance to the team—rather, it was an exercise in pushing technology forward.

Nevertheless, Kor felt an instant rapport with all of the innovators and builders he encountered at the SEMA Show. After all, he and several members of his team are custom, restoration and performance racing enthusiasts themselves.

“I was always nuts about cars,” he chuckled. “We have an affinity with [the industry]. It’s just that, as I get older and on the green side, I think we should do that on the weekend, not as a daily driver.”

Moreover, based on the Urbee, Kor believes that 3-D printing can be a major boon to the automotive industry and aftermarket.

“If we were in a tractor or a bus company or building this Urbee as a real production model with investment money, then I would absolutely think it’s economical to do it this way,” he said. “It frees you up to really design the parts.”

3-D for SEMA Members

SEMA offers members rapid prototyping at its Diamond Bar, California, headquarters. The association’s unit “prints” from CAD files in ABS plastic, and some member companies have already put it to use producing limited-run, user-end parts. |

|

Much of the Urbee’s interior will be “printed” based on computer-assisted design. |

|

“For some applications, our build/print resolution of 0.010-in. is high enough that some of our members have used our service to produce small parts for their end products,” said Oscar Muñoz, SEMA vehicle project data manager. He cited two examples: a battery company that created approximately 500 plugs for its electrical harnesses, and a turbocharging specialist that did a limited run of plastic plates for its performance applications.

“The service is meant to be a way to promote the technology to our members and tie it in with Technology Transfer,” said Muñoz. “Compared to typical prototyping methods that can take up to weeks, our service is able to provide our members with a prototype at their door within a matter of days. For companies—particularly small ones needing to keep R&D costs down—our service provides a fast, low-cost avenue to getting accurate models of their designs for test fitting and, in some cases, functional testing as well.”

SEMA’s promotional rate for all members is $10/cu. in. of material. The service requires a CAD model file, preferably in stereolithographic (STL) format, which is initially processed to calculate the amount of material required to build the piece and produce a quote for the SEMA member. Project turnaround time typically varies from two to five days from start to delivery. Output is in ABS plastic, and the work is performed at SEMA’s headquarters in Diamond Bar, California.

So what are the long-term ramifications for the specialty-equipment industry? If economic and technology experts agree on anything, it’s that the exploding 3-D revolution will be wildly unpredictable for quite some time. Many believe that the technology will further promote the reshoring of manufacturing in America. Others argue that it will make outsourcing easier. Still others see it wreaking havoc on intellectual property, with myriad lawsuits establishing a confusion of new precedents. Counterfeiting of product will almost certainly become a nightmare concern while industry and government readjust to the

new reality.

The die, however, is cast. Three-dimension printing is expected to become a $5.2 billion industry by 2020. Additive fabrication, rapid production, an upheaval for business as we know it—call it what you will, there is no turning back from the future.